A Stranger From the Beginning: Radical Contradictions in the Cinema of Yvonne Rainer

Critics Campus 2024 participant Grace Boschetti explores the career of innovative filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, devoting particular focus to her 1974 feature Film About a Woman Who… and its intimate, unorthodox deconstruction of a woman’s conflicting feelings about her relationship.

I see myself in the same predicament as many artists who identify themselves … with the so-called avant-garde. No matter how overtly politicized my work becomes with respect to subject matter, my thinking and making process will always result in a product that appeals to a very select audience, an audience already disposed to share my point of view.

– Yvonne Rainer, 1976

In the early 1960s, multidisciplinary artist Yvonne Rainer was part of the collective that gathered in the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village, New York. It was a time of fervent experimentation: exercises in upheaving a standard vocabulary of movement. Motivated in part by a desire to transcend what she perceived as the “narcissistic-voyeuristic duality” inevitably existing between dancer and spectator, Rainer made the leap to film – a medium she felt better allowed for individual experiences to become shared emotions.

At the beginning of her filmmaking career, Rainer was interested in abstracting melodrama. Seeking to divorce the presentation of emotional and sexual conflicts from dramatic constraints, the director defined her characters and narratives loosely; interactions were less acted out than simulated. With her debut feature, Lives of Performers (1972), she constructs a love triangle between three rehearsing dancers in a Brechtian satire of narrative. The self-conscious instinct to undercut sincerity is balanced by moments of piercing beauty: among them, a mesmeric solo danced by the late Valda Setterfield, and a tender letter in which one of the performers (Shirley Soffer) resigns herself from being loved by someone who is unwilling or unable to make up his mind.

Film About a Woman Who… (1974), Rainer’s second and most widely celebrated feature, likewise concerns a woman’s rage at a male lover. In her ambiguous approach, the four principal actors (Soffer, Renfreu Neff, Dempster Leech and John Erdman) are identified only as “she” or “he”. A series of unwieldy recollections are relayed through a combination of narration and intertitles, Rainer occasionally switching between these modes of communication mid-speech; in certain instances, words are omitted to render sentences incomprehensible. The reflections are melodramatic, mournful and often neurotically funny. The righteous anger of the nebulous, unnamed titular character is punctured by a bitter understanding that, on some level, she is complicit in her own subjugation.

As in Lives of Performers, Rainer’s status as a dancer and choreographer once again informs her direction. Both her debut feature and Film About a Woman Who… are beautifully photographed by cinematographer Babette Mangolte, best known for her collaborations with Chantal Akerman. The use of space within frames bears suggestions of attraction or antagonism; for instance, a memorable beach-set composition places the distant figure of Erdman in the gap between Soffer’s foregrounded limbs. In the brief segment that follows, Rainer plays with motion and stillness: Edrman, Soffer and a child (Soffer’s daughter Sarah) repeatedly pose mid-movement for extended stretches in an amusing caricature of familial candidness.

The film’s most pronounced chapter, “An Emotional Accretion in 48 Steps”, lays bare the emotional paralysis at the story’s core. In a rare instance of spoken dialogue, the woman (embodied by Neff) asks to be held by her lover (Leech), even though she is dissatisfied with him. This leads to sex. In the day and night that follow, she begins to feel worse, but does not express this to him. The segment builds to its operatic crescendo, revealing the woman’s anger and her sense of having betrayed herself by inviting intimacy when, in reality, “she had wanted to bash his fucking face in”.

Film About a Woman Who…

Similarly, in a later passage narrated by Rainer, the woman describes being encroached upon by the man and obliging him, all the while fuming in silence: “When he unconcernedly, or calculatingly – she couldn’t tell which – shifted his position so that his knee grazed her thigh, she carefully disengaged herself from contact. By the time they arrived in town, he occupied most of the seat, and she had squished herself into a cramped, tight ball. She was enraged.” Accompanying this anecdote are still images from the shower scene in Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), echoing Rainer’s use of the similarly gruesome Pandora’s Box (Georg Wilhelm Pabst, 1929) in Lives of Performers.

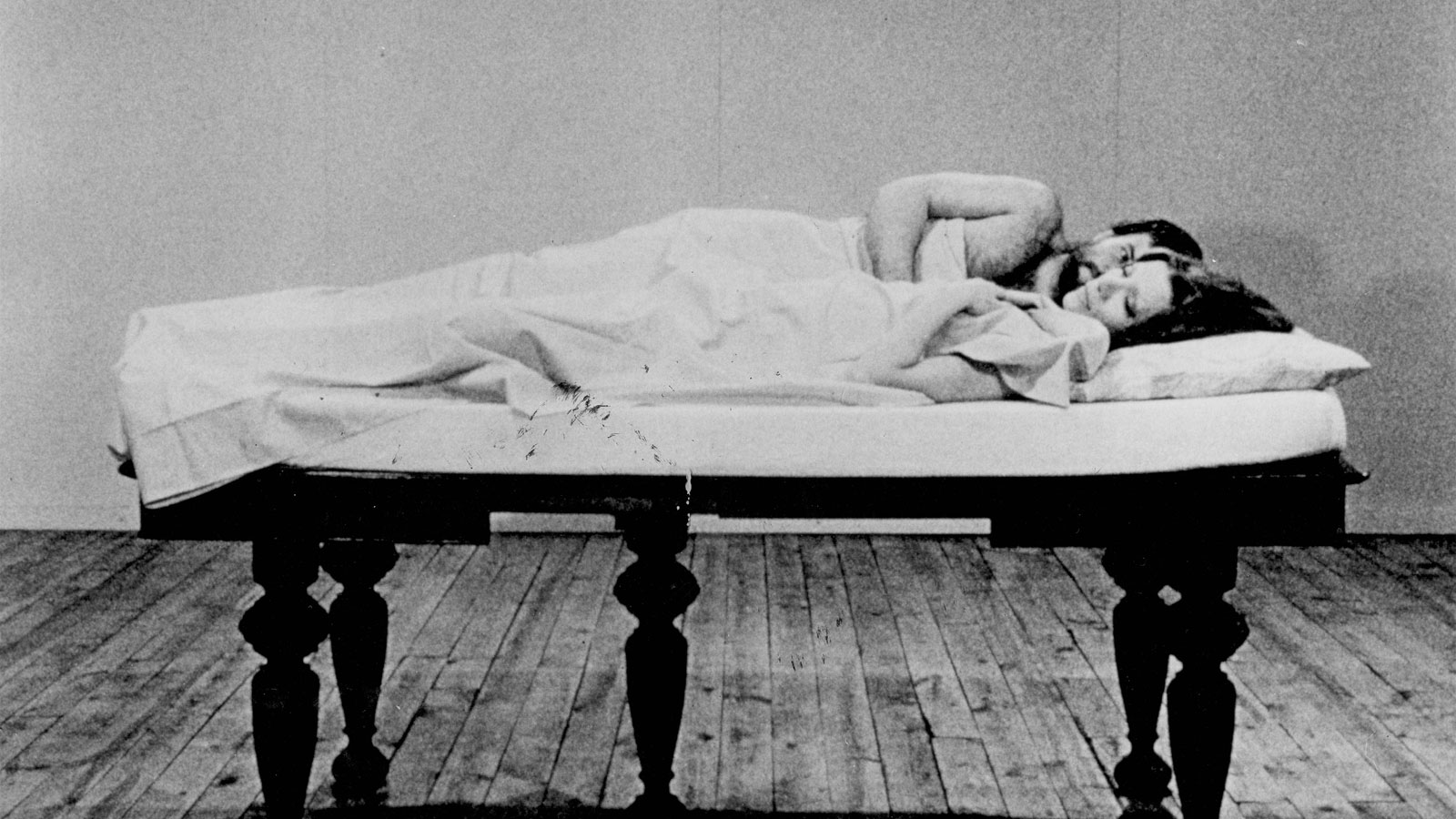

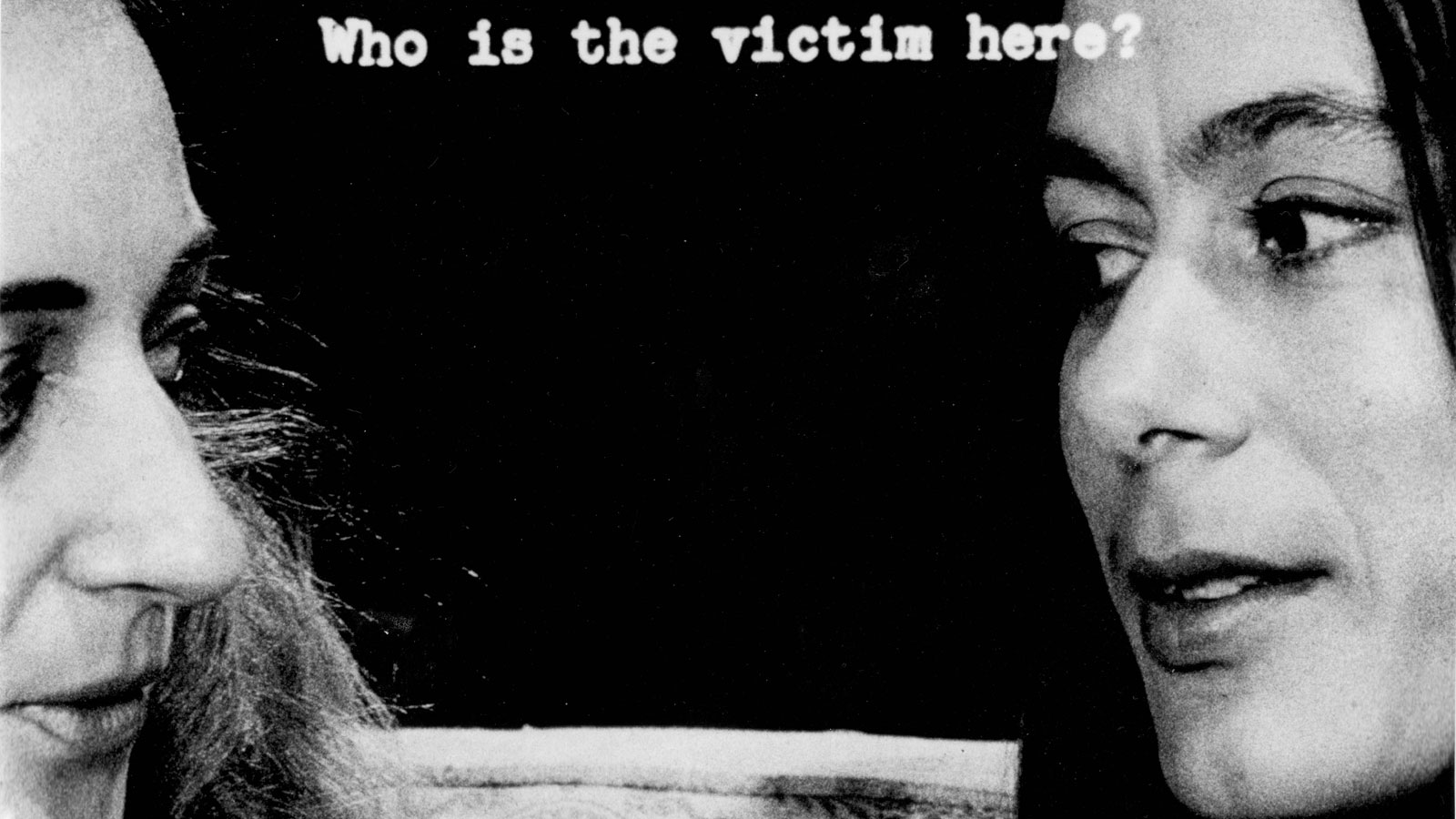

Another section, introduced with the text “Who is the victim here?”, announces a woman to whom Rainer’s narration ascribes a “delicate, precise and lilting” voice, which her protagonist would usually regard with disdain. This first woman divulges a private sexual fantasy, which is then enacted – a performance of exhibitionism and feigned victimisation. Neff is languidly undressed by Soffer and Leech; as she presents her foot or wrist to each of them, the corresponding article of clothing is removed. Finally, in an excruciatingly slow take, Leech pulls her underwear to the ground, exposing Neff completely. As he begins to re-dress her, the camera shifts position, closing in on Rainer. Her face is pasted with newspaper clippings, excerpts from Marxist activist Angela Davis’s private letters to the then-incarcerated George Jackson. These constitute a more insidious form of public exposure: vulnerable expressions of love violated in the act of prosecution.

As per the subtitle of MIFF’s retrospective program, Rainer’s films could be considered, by her own description, “autobiographical fictions”. In the opening of her third feature, Kristina Talking Pictures (1976), Rainer conceives a heroine who is inspired by the works of Emma Goldman, Virginia Woolf, Martha Graham and Jean-Luc Godard to leave behind her “lion act” at the circus. Knowing the traces these figures have left on the director’s own body of work, I initially inferred that she was speaking of herself and her pathway to filmmaking; later, however, I found an interview in which she insists that this was only a statement for rhetorical effect, advising, “You can’t believe anything I say in the first person in my films.”

Whereas Film About a Woman Who… in particular endures as a masterful expression of anger and catharsis, Rainer veered more overtly into discursive political terrain with her 1980s output. The cerebral Journeys from Berlin/1971 (1980) meditates on revolutionary violence, while The Man Who Envied Woman (1985) uses the skewering of a philandering, purportedly left-leaning and feminist male academic as the catalyst for wide-ranging theoretical discussions. The late phase of Rainer’s filmmaking career yielded the genuinely radical Privilege (1990) and the charming MURDER and murder (1996).

As Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote in a 1978 article on cinematic avant-garde innovators, “Obscurity and ambiguity aren’t so much obstacles to an appreciation of [Rainer’s] films as integral parts of their enjoyment.” My sincere hope is that those inclined to experience Rainer’s films for the first time, either at this year’s MIFF retrospective or elsewhere (gratefully, her films can be accessed online), may discover a body of work that is challenging, resonant and enlivening.